Read Time: 8 Minutes |

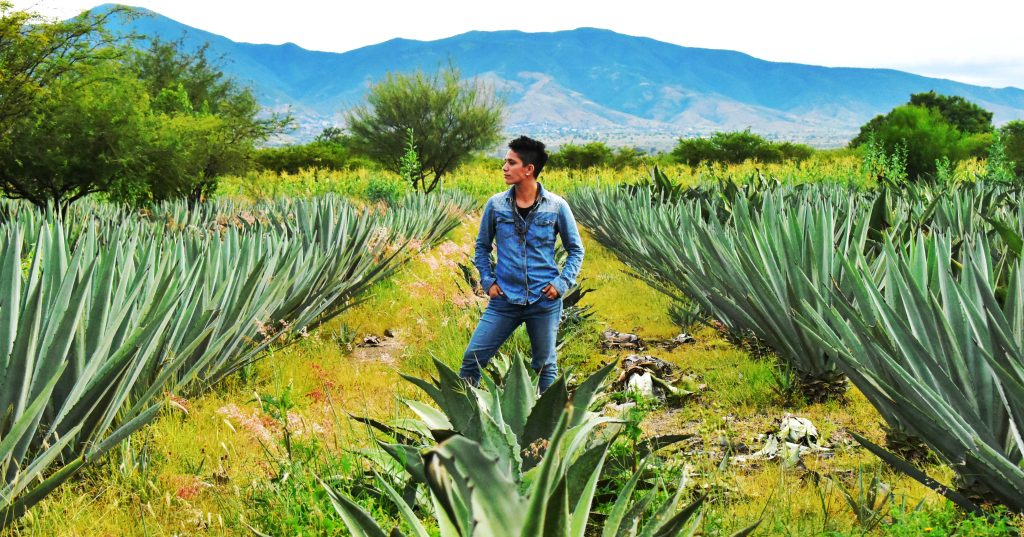

The tequila industry is booming. But can the land and the ecosystem where the precious agaves are harvested, as well as the farmers, sustain this explosive growth?

| By Cameron Mowat

America’s first native spirit is back in fashion. Tequila had been steadily rising in sales throughout the 21st century on the back of a soaring increase in quality across the category. It wasn’t until the Pandemic that sales really exploded.

This might seem surprising, as you might expect that with bars closing all around the world that people’s consumption of the usual tequila shots and margaritas would drop off and so too would tequila sales.

However what the pandemic and its attached isolations did was bring tequila into the home in a way never seen before. Homemade Margaritas became all the rage as people chased the flavours they’d grown accustomed to in the bars. House parties flourished and tequila became a staple ingredient for a successful night spent at home rather than out on the town.

Pernod Ricard saw a 60% increase in sales of their tequila brands like Avion and Altos, and many other brands saw similar figures, Patron with 52% and Codigo 1530 with a shocking 94%. E-commerce is a wonderful thing for spirit sales when everyone is stuck inside.

On the back of this stratospheric growth for the category is a significantly higher demand for the plant that tequila is made from – Agave.

Agave is a complicated source material. It is a massive plant, in the cacti genus, that requires a large amount of space, soil and nutrients to grow, and specialised farmers known as ‘jimadores’ to harvest them. It also takes anywhere between 7-10 years for the most sought after agaves to mature and ripen sufficiently to be harvested for tequila production. Some rare subspecies can take up to 30 years to be usable.

Because of these complications, agaves are incredibly valuable and incredibly time consuming. They’re also in incredibly high demand when tequila is booming, which leads to intense pressure on the farmers to grow as much as they can and harvest as early as possible, sometimes even earlier than they should. The consequences of this rush to meet demand are far reaching.

A History Of Heavy Regulations

The Tequila industry is notoriously well regulated, and for good reason. As such an important export to Mexico and a crucial part of Mexican culture, ensuring quality and securing the cultural rights to the liquid has been the mission of the Mexican government since the 1970’s when the Tequila Regulatory Council was put in place.

One of the major limiting factors of the tequila industry surrounds the ‘Blue Agave’ also known as ‘agave tequilena’. To be considered a 100% or ‘puro’ tequila, producers must make all of their tequila from the blue agave, which has been considered to be the best of the best since Sauza first created Tequila using it back in the 18th century.

Because of this, so much land has had to be dedicated to the growing and farming of this one specific type of plant, and prices and demand for it increase in tandem with the growing demand for quality tequila.

Balancing Risk And Reward

To keep up with the demands for blue agave, agave farmers have turned to cloning the blue agave using mono-cultures, transplanting a section of the roots of agave they currently have growing to skip the step of natural seed growth and pollination.

This causes a severe issue in the cloned agave crops. Lack of genetic diversity. Pollination through insects and bats (the unsung heroes of the tequila industry) allows for genetic diversity and therefore higher chances of characteristics like: disease resistance and tolerance to drought. However cloning spreads the same genetic characteristics across all the plants, so if one is at risk of disease, they all are.

This was seen most notably in the 1990s, when a fungal infection burnt through Jalisco (the main region for tequila production where 85% of blue agaves are grown), decimating the agave crop there.

The faceless and emotionless avatar of Global Demand however, cares little for biodiversity in the wake of fattening profit margins. Risking crop loss is just one of the many risks that the industry is willing to take to meet consumers’ demand for the agave spirit.

The bats previously mentioned are key parts of the delicate ecosystem in Mexico. For them to feed and in turn pollinate, they need the agave to flower. When an agave flowers however, it is past its ripening stage and therefore past prime harvesting time. This means that farmers trying to meet their ever growing quotas of supply will tend not to allow the flowering to take place, harvesting before the plant can pollinate. The ecosystem suffers the consequences.

Compound that with the deforestation to make room for agave fields, and the terraforming of the wild areas of Mexico, and you begin to paint a picture of a looming ecological crisis. Sprinkle in the increasing use of toxic pesticides and chemical fertilisers to speed up growth and maturation of the agaves and the picture gets grimmer and grimmer.

The Price Paid By The People

Profit brings people. It’s no secret that as an industry like tequila becomes more and more popular it will draw the attention of outside investors looking for their slice of the pie.

Land that can be used to harvest agave is as valuable to the industry as the agaves themselves. Bigger brands will do their best to buy outright or rent agave fields for decades in advance, staking their claim to all the agave grown there and controlling the production quotas.

The increase in the demand for land increases its cost. This pushes local farmers and smaller, artisanal producers further and further out of the industry as they become unable to compete with the bigger brands with their eyes set on supplying global demand no matter the cost.

Many ‘agave activists’ point to this as a form of neo-colonialism, as foreign investors race to buy up as much land as they can at the expense of the Mexican people that have been caring for and cultivating the land for generations.

Indeed the local farmers are being put under intense pressure to meet quotas whilst smaller local producers are being forced to either sell their land or reduce the quality of their product, both by harvesting agave early and therefore using substandard raw material to keep their costs low enough to compete with the new wave of global suppliers.

It’s a tale as old as time, those that suffer the consequences of industrialisation and the rampant pursuit of capital are the people without the resources to weather the storm and the land itself.

Mezcal To The Rescue?

Many point to the saviour of this dire situation as being Mezcal, as well as its cousin spirits Racilla and Sotol.

This is because Mezcal does not have the same rules and regulations imposed on it as Tequila. Up to 57 different agaves can be used for Mezcal, which allows for far greater biodiversity in its crop, as well as the added benefits of having far more expressions of flavour in the liquid.

Mezcal does not have even nearly the same level of global popularity as tequila, but it’s getting more and more notice and also experienced some rapid growth riding the wake of the tequila boom. As producers struggle to meet the consumption of tequila, it’s possible for mezcal and its cousins to slip in as a replacement for tequila if and when supply can’t meet demand.

While it might seem that Mezcal taking the pressure off the tequila industry is the saving grace, locals in the main mezcal producing region of Oaxaca and small batch artisanal mezcal producers are nervous.

To many, the problems in the tequila industry are a cautionary tale, and a warning of what’s to come. As Mezcal becomes more globally sought after it will naturally be subject to more regulation and higher taxes. Many will not be able to afford to adhere to these regulations and be unable to survive because of it.

Part of mezcal’s charm is its grassroots characteristics, with many mezcal distilleries being buried in the wilder parts of Mexico and requiring guides for people to even find them. This aspect will be the first to go when Mezcal becomes the new gold rush for agave spirits. Some locals point to the similar deforestation and terraforming that Jalisco experienced beginning to happen in Oaxaca even now, as investors rush to lay down the most popular agave, the Espadín, in preparation for future growth.

The Endless Cycles Of Boom & Bust Have To End Somewhere

Tequila is an industry that can be characterised by cycles. The most notable is the boom and bust cycle. This isn’t the first time that tequila has experienced a boom, and if history is any indicator of the future it means a bust is on the way. During the boom, agave is in high demand and with that all the consequences, positive in terms of sales and negative in terms of the effects on the people and land.

But after the boom, when global demand inevitably shifts down a gear and a new spirit trend surges to take its place as the ‘drink du jour’, it is the large-scale producers and distributors that will feel the effects the least. Agave prices will devalue and the farmers will pay the difference of the price that the land has already paid. It’s possible that the land, and the wider eco-system will eventually not be able to sustain the growth of the industry, placing a dark ‘cap’ on the tequila market that will have lasting and far reaching drawbacks on both the economy and ecology of Mexico.

However the situation is not without hope. A group of growers and distillers have signed on to the programs like Tequila Interchange Project and the Bat-Friendly Tequila & Mezcal Project, which encourages the production of ‘bat friendly’ tequila, helping to reintroduce the long-nosed bats as the principle pollinators for their fields. They do so by allowing 5% of their agave to naturally flower every crop cycle, awarding them a label of recognition for their efforts.

Some producers, notably Patron, have also issued ‘guaranteed contracts’ which set a fair minimum price for agave no matter the market cost, helping to support the farmer when prices drop.

All in all, change is needed to break the cycle. There are many forms this change could take, some better than others. One spirits industry that might show tequila the way is the Japanese Whisky Industry. It handled its dwindling supply of liquid by shifting gears away from age statement whisky, and focused more on exciting blends that express the variety of the Japanese whisky’s character. Tequila may have to take a similar approach, potentially shying away from its over reliance on Blue Agave, or investing far more in sustainable practices.

Either way, something needs to change before the industry finds its growers, producers and land burned out beyond repair.